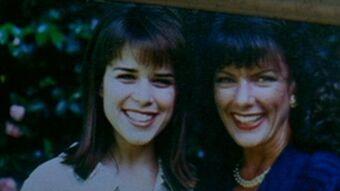

In what is perhaps the most chilling scene of the Scream series, Sidney Prescott (Neve Cambell) lies asleep on the couch in her secluded home, tucked away from the horrors of her past. On a side table sits a framed picture of Sidney and her deceased mother, Maureen Prescott (Lynn McRee). In the photo, Maureen commands our gaze. Her wide smile is twisted into a grin more sinister than joyful as the peaceful tone shifts into something high pitched and threatening. We are meant, it seems, to fear her. Outside, between the thick barrier of trees and beyond the veil of fog, Maureen creeps forward. She crosses the fenced threshold of the ether, back into Sidney’s consciousness, where she is most alive. For once, the villain takes its time. There is a harsh tonal shift of the scene that feels almost out of place for the normal meta-slasher approach of Scream.

Normally, Sidney’s attackers approach in hectic motions. When they are seen, they duck out of view, toying with Sidney’s concept of reality. They are desperate, Maureen is determined. Her slow steps refute the terror of a double take. Sidney, in her dream state, is unable to run. It is the first time Scream offers us up a real phantom, a perfect ghost amidst the mask-wearing imposters. And this ghost brings a risk far more insidious than the physical, virale threat of a knife. In the vault of Sidney’s mind, her mother is meant to be kept neatly locked away. Maureen takes her place at the window and speaks slowly, commanding Sidney to pay careful attention. Her words spill out and fill the room in a ghoulish echo, “Everything you touch Sid, dies”. She doesn’t need the pageantry of a chase to bite a curse deep into Sidney’s thick skin: “You’re poison. You’re just like me”.

As her black, rotten fingers slip down the window, Maureen whispers a warning before returning once more into the earth: “They’ll do it to you, too”. Out in the wilderness, by exile of her own design, Sidney is unable to escape from what haunts her most. A fear worse than death is reflected in the window: repeating the cycle and becoming her mother.

Sidney’s hero story isn’t about thwarting off serial killers, it’s a journey through the grieving process. The real villain of Scream is more ethereal and complex than a jilted ex-boyfriend. It’s the ghost of Maureen Prescott, and all of the scars she left behind.

It’s no secret that Sidney Prescott is widely regarded as an integral player in the Final Girl arsenal. She’s quick witted with a firm resolve, which is a departure from wall-flower victimhood in horror. She ditches the guy, grabs the gun, and survives. So, sure, she deserves her flowers as a gleaming example of a (dare I say it?) girl boss. But a less flattering principle of the Final Girl Formula is mom-issues (or, more succinctly, the rejection of maternal instinct, but that’s a whole other article) and Sidney is certainly no exception. She’s a girl with her guard up, which constantly puts her at odds with her deep desire to trust. The shadow side to her bad-assery is that it grows from hostile soil. She’s handles assaults on her life with a breezy disposition that plays as confidence, but hints at a past where she had to learn how to disconnect long before she was the celebrity victim in a series of pulp murders. When you linger, you realise that Sidney isn’t ahead of the curve, she’s floating above it, completely untethered from reality. In the right light, dissociation can look a lot like an unapproachable sense of cool.

In each round of murders, Sidney is ultimately asked to pay for the sins of her deceased mother. The suffering she endures is empty target practice for a body that is no longer around to take the hit. Her victimhood is secondhand, which is often the case when futile rage has nowhere else to go. The specific brand of anger that Sidney absorbs is toxic masculinity personified: weak hearts without the bandwidth to process tough emotions, who never learned the recess-lesson that being hurt isn’t an excuse to hurt someone else.

(And yeah, some of Ghostface’s hosts were women. But it’s 2020 baby, anyone can be a misogynist).

Sidney is a vessel for the inheritance of generational trauma, and her biggest obstacle isn’t outrunning the swing of a knife, it’s getting cosy and unearthing what made her that way to begin with. Each iteration of Ghostface brings with them new insight to the woman her mother was, and Sidney is left to breathe new meaning into the hollow shape in her past.

Maureen was a woman with dreams of a life bigger than the city limits of Woodsboro. To the men she left empty, she was a succubus who couldn’t be happy with what she was given. Maureen left town as a wilful teenager to chase her dreams in Hollywood (adopting the stage-name Rena Reynolds), only to be cast out by a hierarchy that asked too much of her. After carrying a child as the byproduct of an assault, Maureen retreated to the life she once rejected to reclaim a sense of stability. Back in Woodsboro, she did her best to acclimate: nuclear family, white picket fence, but she was destined to fail. She was a woman with a penchant for taking and a forgetfulness to give. When she was murdered, that was all Maureen left behind. Any duality she held inside her was evaporated, leaving behind the flat outline of a mother who wasn’t good enough. This narrative, crafted by men who feared her ambition, went down smooth without Maureen around to defend herself. Following this path of thinking, it is easy to draw parallels to society’s brash categorisation of women as a whole. We leave very little space for women to be bad mothers and wives, and also good people. Maureen’s worth was knotted up in her service to others, rather than her commitment to herself. Our expectations of women are often miscalculated as absolute truths, and when our truths are put to the test, we can adapt or we can revolt.

Ghostface is nothing but a rotating door, who’s mask ultimately personifies the facelessness and interchangeability of its wearer. In horror, “the mask” often represents the godlike nature of the soul that gives it power. But in Scream, the mask is much more utilitarian than all that. It’s murderers are distinctly, frustratingly human. Boys with mom issues, moms with issues with other moms, boys with mom issues (again). The mask doesn’t make them powerful, the anonymity it provides makes them meaningless. To Sidney, Ghostface is the only tangible way that she is able to fight through her anger, resentment, and sorrow. It is an embodiment of the walls she has built up to protect herself from the truth she needs to move on.

For Maureen, Ghostface is a physical manifestation of the daily violence enacted by fragile egos when their world view is tossed asunder. It is a boogeyman for the autonomy we deny women, and for the blame we prescribe to them to make things easier on ourselves. It is man’s ability to feel so emboldened by their own personal anguish, that they turn it into violence.

Sidney and Maureen are different women, whose common thread is their desire to be known and witnessed as fully formed individuals. But unlike her daughter, who’s particular disdain for the limelight pushed her into hiding, Maureen was a moth to the flame. The theatricality of the Woodsboro murders seems like a special touch from Maureen herself. Six feet beneath the chaos, the girl next door finally brought fame back home.

Sidney, in her own way, follows in her mother’s footsteps . She leaves town, rejects the expectation to play it safe, and refuses advice that doesn’t stick. After coming back from a trip that leads her to the darkest pieces of her mother’s past, Sidney leaves the door unlocked and the gate to her home wide open. What was once kept at a distance, peeking in through a window, now has permission to stay. There is space, finally, for the truth of her mother in all forms. Sidney doesn’t try to prove that her mother didn’t make mistakes, or that her reputation was purely slander. She lets it all in, and adds it to the family portrait, putting beauty in the details. In that way, Maureen is given the peace of a new life, and Sidney is allowed to make room for her own.

by Mackenzie Bartlett

Mackenzie Bartlett (she/her) is a filmmaker and non-profit community arts administrator from Portland, Maine (and also actually just three eels in a trench coat). She feels a spiritual connection to the use of Nick Cave’s ‘Red Right Hand’ in the SCREAM series. When she isn’t screaming about horror into the ether, she can be found bent over a sewing machine or looking at pictures of frogs. Her favorite films are haunted VHS tapes that curse you when watched. You can find her on twitter @mcknzybartlett

Mackenzie Bartlett (she/her) is a filmmaker and non-profit community arts administrator from Portland, Maine (and also actually just three eels in a trench coat). She feels a spiritual connection to the use of Nick Cave’s ‘Red Right Hand’ in the SCREAM series. When she isn’t screaming about horror into the ether, she can be found bent over a sewing machine or looking at pictures of frogs. Her favorite films are haunted VHS tapes that curse you when watched. You can find her on twitter @mcknzybartlett

Leave a comment